The Light Rail Transit 1 or LRT-1 runs from Roosevelt in Quezon City to Baclaran in Parañaque, covering an almost 20-kilometer route. In 2021, an estimated 44.35 million commuters took the LRT-1. It was the second busiest line among local railways that year after the Metro Rail Transit Line 3 (MRT-3). Despite being marred with inconveniences that have discouraged the riding public from taking it, MRT-3 still tallied a 45.6 million annual ridership in 2021 amid the pandemic.

The LRT-1 opened to the public in 1984. It was the first overhead railway in Southeast Asia, although it could have been a street-level train had the government followed the 14-month study funded by the World Bank from 1976 to 1977. Instead, the Department of Transportation pushed to raise the train’s platform to avoid building over many of Manila’s intersections.

The LRT-1 could have been a lot of things, it turned out.

What could have become of the LRT-1

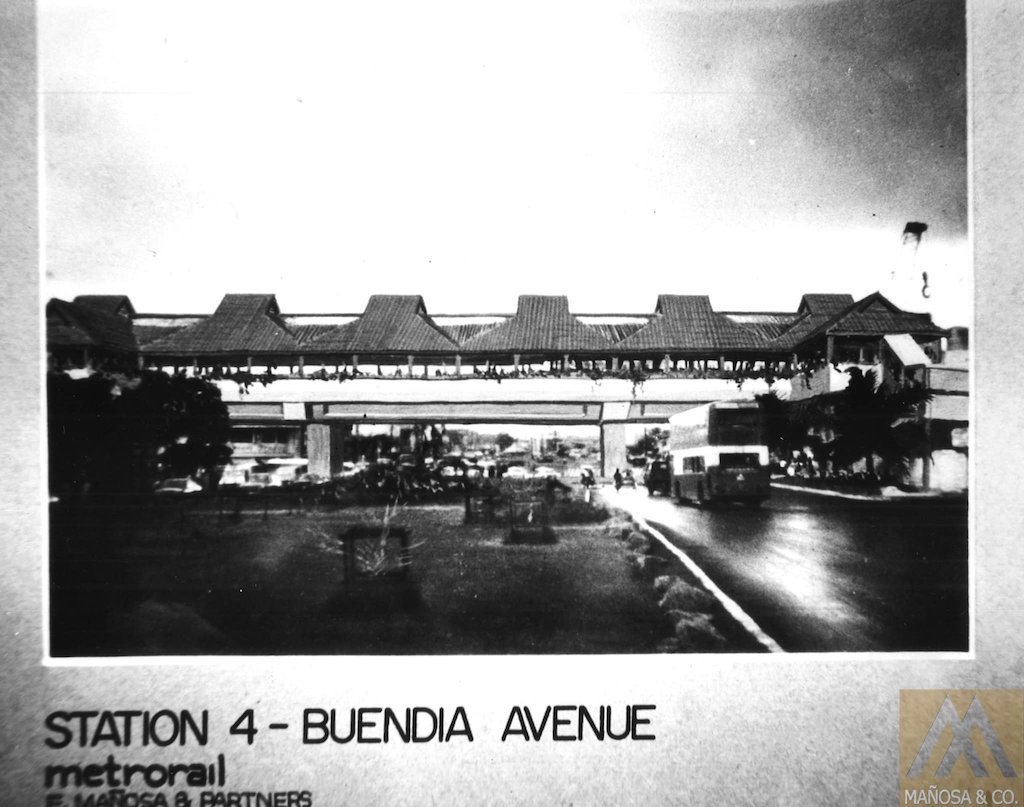

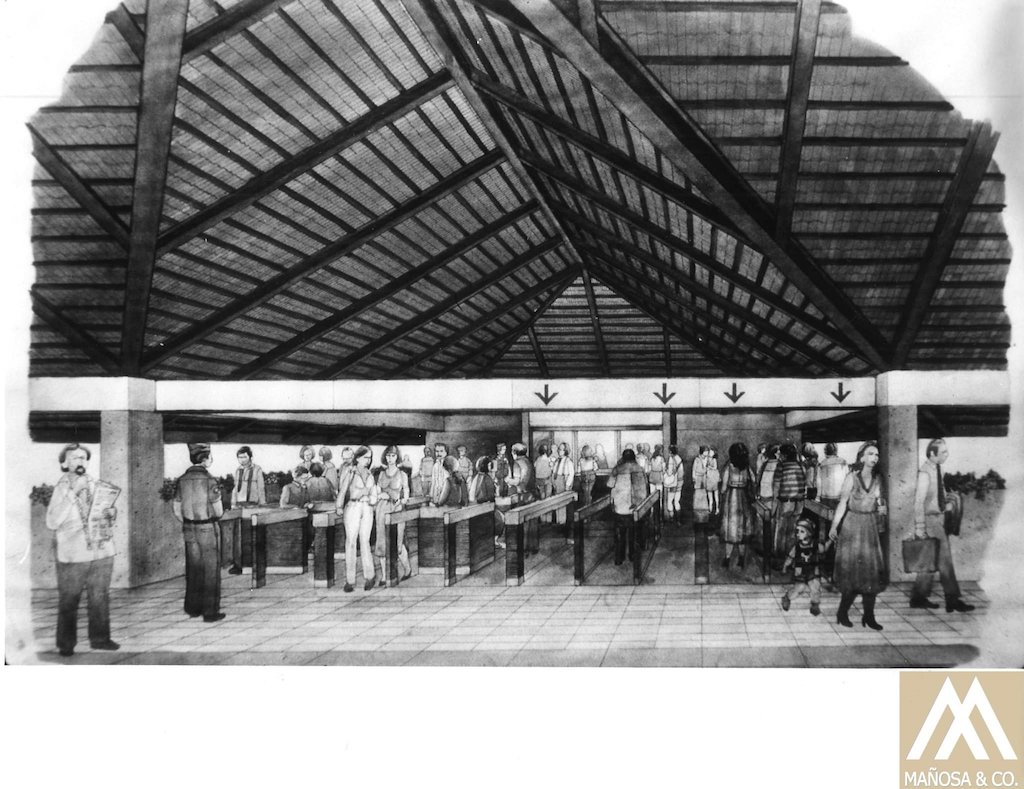

Designed by the National Artist for Architecture and Allied Arts Arch. Francisco “Bobby” Mañosa in the 1980s, the LRT-1 elevated railway stations were built to look like a Bahay na Bato, a prominent type of housing structure during the Spanish colonial era that succeeded the Bahay Kubo.

[READ: Growing up in my dad’s studio: A glimpse into the lives of Nat’l Artists with their children]

“The vision was to create a station that was tropical, climatically responsive, and truly spoke to our local culture through an architecture that is uniquely Filipino,” the architect’s namesake firm Mañosa Company said in a Facebook post. This explains the prominent features of LRT-1’s stations, which include its distinctive raised terracotta tiled roofing that sets it apart from other local train lines whose designs are closer to modern architecture.

Sticking to Filipino architectural elements—precisely that of the Bahay Kubo—is, after all, Mañosa’s bread and butter. He’s well-known for the tropical-Baroque Tahanang Pilipino that came into completion in 1978 and soon became the Coconut Palace, which is ultimately a Mañosa study in indigenous materials, specifically coconut.

But perhaps a forgotten trivia about the Mañosa-designed LRT-1 is that the architect had other intentions for the railway besides mobility. In the same Facebook post, the Mañosa Company revealed that in his designs, the late National Artist integrated provisions for green energy alternatives such as solar panels as well as rainwater collection.

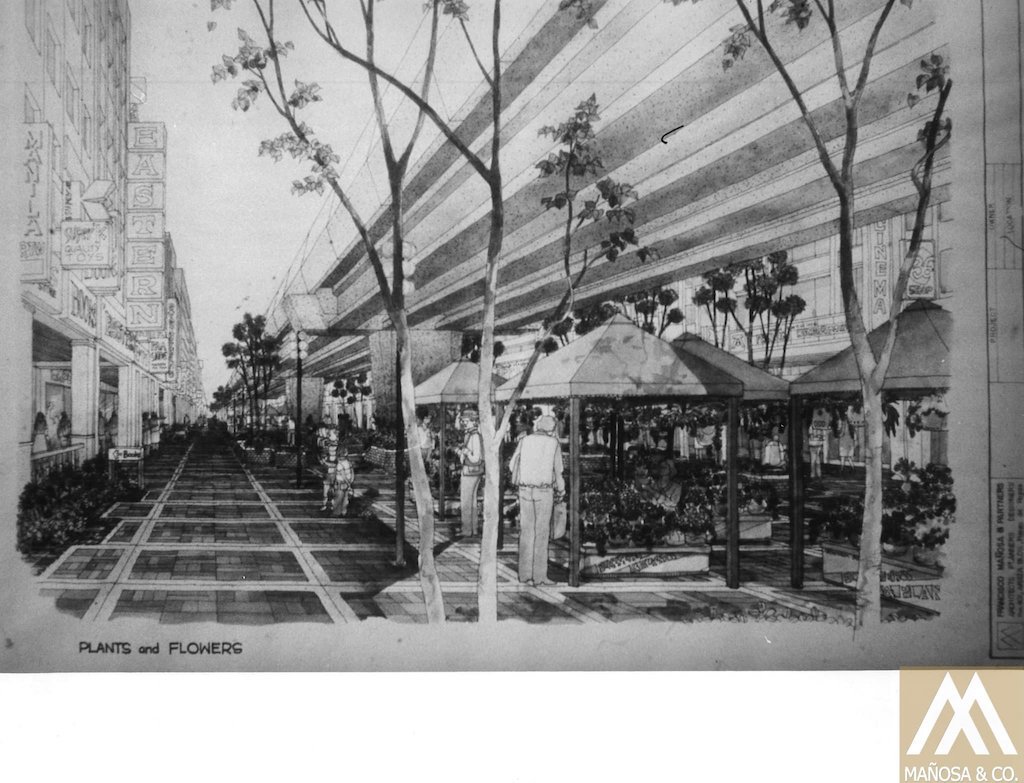

Mañosa was a rather involved architect, it turns out. It is said that he oversaw even the smallest details, including designing the colors of the trains themselves (LRT-1 was originally referred to as the Yellow Line and has—to this day—yellow train cars. It was reclassified as the Green Line in 2012). The National Artist proposed ideas for other parts of the train, too. The post was also accompanied by black and white photos of the stations during its early days together with illustrations that reveal plans that Mañosa had for the underbelly of the LRT-1 railway.

“The importance of public spaces and ‘pedestrianization’ was also being proposed underneath the station,” the post read. It added that much of the challenge was trying to convince the Ministry of Public Works and Highways (renamed in 1987 and now known as the Department of Public Works and Highways or DPWH) to sign up for such progressive pro-pedestrian ideas.

[READ: The case for a pedestrian-centric alternative to PAREX, according to urban planners]

In order to make space for shops, art galleries, outdoor cafes, bookstores, and other places of recreation underneath the railways, major roads would have to be closed, a concession the ministry was unlikely to make as it was the very thing it was trying to avoid in the first place: disrupt major roads, hence the decision to make LRT-1 an elevated railway.

A consolation

[M]ass transit being the thing that ferries us to and from the first and second places of our lives is the perfect intermediary and could very well be more than a literal means to an end but an end in itself.

Today, save for select stations, underneath some LRT-1 tracks are mostly busy roads, especially the ones along Taft Avenue. The northern stretch of the line is far luckier. In Carriedo, the station connects to a vibrant commercial center and paths that will lead you—a few hundred meters later—to the historied districts of Escolta and Binondo.

The closest approximation of Mañosa’s vision of a pedestrianized LRT-1 station might be the Central Station.

With the redevelopment of Arroceros Forest Park and the Metropolitan Theater—both are within walking distance from the Central Station—the underside of that part of the LRT-1 is alive more than ever. Just in the Arroceros area alone, there is ample space for leisurely activities and even a cafe, mind you. Heck, there’s even WiFi (and somehow a koi pond? In the forest?).

I am reminded of this idea of a “third place”, a term coined by urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg to refer to “public places on neutral ground that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home (first place) and work (second place).” And mass transit being the thing that ferries us to and from the first and second places of our lives is the perfect intermediary and could very well be more than a literal means to an end but an end in itself.

It may be hard to think of the LRT-1 as more than just a means to move from one point of the city to another. The grueling commute makes it doubly harder as we are wont to dissociate in moments of discomfort. The thought of what could have been a greener, pedestrian-centric version of the LRT-1 could’ve made it a lot easier.

The post Did you know that LRT-1 was designed to have bookstores, galleries, and cafes underneath it? appeared first on NOLISOLI.

0 Comments