“Pretty Soon You’ll Be Able to Afford Things Again,” a story on a US-based publication posits, basing this on the gas price slump in the last 50 days or so. Reports from major economies like the US and China point to an optimistic easing of inflation as energy raw materials—the main culprit for the surge in consumer prices in the last months—are getting cheaper.

In the Philippines, however, it seems like we are far from the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. From a low of 3.0 percent in January this year, inflation has continually risen to 6.4 percent as of last July.

Meanwhile, minimum daily wage in NCR increased only by P33 in June (P570 for workers in the non-agriculture sector and P533 in the agriculture sector) days before President Rodrigo Duterte stepped down. The adjustment comes more than three years after the last increase was implemented for workers in private establishments in Metro Manila.

In the latest Social Weather Station Self-Rated Poverty survey, according to 1,500 Filipinos 18 years and older, P15,000 is the minimum monthly budget that a family needs to consider themselves “not poor.” To live comfortably past the poverty line, the National Economic and Development Authority estimated that a Filipino family of five would need an aggregate income of P42,000 a month, assuming that said household has two family members earning P21,000 each.

But that was four years ago. Today, families would be lucky to even have one employed family member as nearly 3 million Filipinos were unemployed in June 2022, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority’s latest labor force survey.

How inflation affected prices

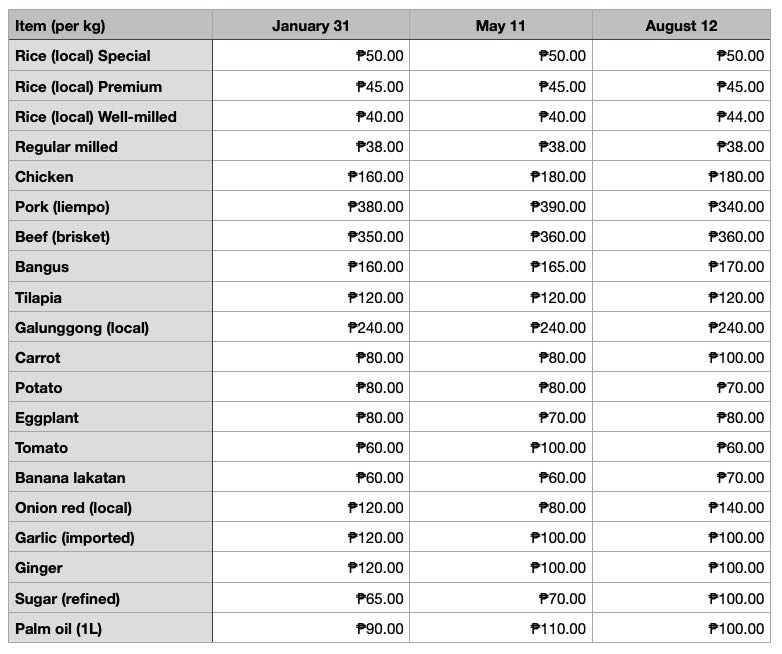

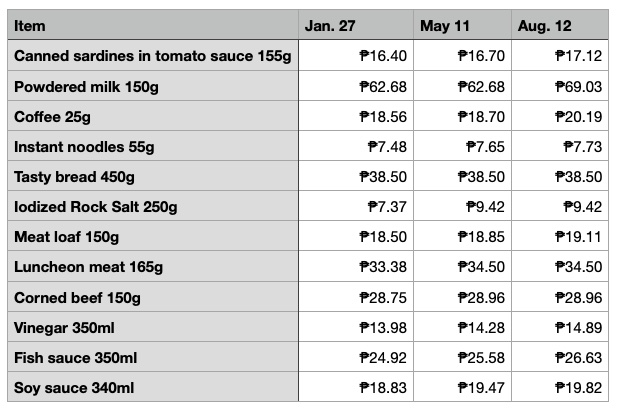

The effects of inflation are most felt by common Filipinos through everyday prices. And to illustrate this, we looked at data from the Department of Agriculture (DA) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) from the past few months.

Consulting prevailing and suggested retail prices, we took a glimpse at the small and big changes to our grocery and market bills. The biggest price jump is with refined sugar, which was only P65 per kilo in January but skyrocketed to P100 per kilo in August owing to a sugar shortage. This crisis will also likely result in price increases in beverage and processed food products, said the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Surprisingly, despite sugar being one of its primary ingredients, the suggested retail price of bread based on DTI data stayed stagnant from January to August at P38.50, but only because the prices already reflected a historic P3 hike in certain bread brands—a first in six years—implemented in February.

Well-milled local rice price also increased by P4 per kilo in the last three months from P40 to P44, according to DA’s prevailing prices list.

Most grocery store items classified as basic necessities and prime commodities also increased their prices, from canned goods to condiments, but only by a few pesos. Some items that managed to weather the inflation have either shrunk or caused big companies to absorb the extra costs and therefore take in losses.

Here’s a detailed look at the prices of these goods:

Prevailing Retail Prices in Pesos (P) of Select Agri-fishery Commodities at NCR Markets

Average Nationwide Suggested Retail Prices in Pesos (P) of Select Basic necessities and Prime commodities

Disclaimer: This data set only covered selected basic and prime necessities as defined by DTI. Basic necessities are goods vital to the needs of consumers for their sustenance and existence in times of any of the cases provided under Section 6 or 7 of the Republic Act 7581 or the Price Act. Prime commodities are goods not considered as basic necessities but are essential to consumers in times of any of the cases provided under Section 7 of RA 7581.

The post Here’s how much basic commodities’ prices have changed—in 2022 alone appeared first on NOLISOLI.

0 Comments